19 世紀英國女性探險家伊薩貝拉‧露西‧博德(Isabella Lucy Bird,1831 - 1904)曾在她的旅日見聞名著《日本奧地紀行》(Unbeaten Tracks in Japan,1881)如此描述:「車伕上衣總是在身後飄揚,露出紋著精緻神龍與魚類圖案的前胸後背。日本政府最近禁止紋身,但紋身不僅是廣受歡迎的彩繪習俗,也可以替代容易破敗的衣服。」[1]這是伊薩貝拉僱用人力車進行日本在地巡禮時所觀察到的景象。

《人力車》這幀手工上色的蛋白照片中,一名高壯車伕手撐著車駕,後頭載著一位身著和服的女子。此景在伊薩貝拉的時代十分常見,然而與她所敘述的不同在於:照片上這名男子並未著裝,他的身上僅穿戴一條丁字褲與斗笠,裸露至少八成肌膚,身軀紋著盤旋的龍與人物。通常,人力車與日本和服女子搭配之題材的蛋白照片相當豐富,但裸露軀體的車伕相對而言便十分罕見了,這正是此張照片勾人興味之處。

一般車伕照片經常表現其面容、拉車動作或場景。有時他們像某種人類學紀錄影像,被安置在毫無景深的攝影棚布景中。《人力車》中,車伕的頭背向鏡頭,覆缽狀大斗笠遮蓋了臉,體態作勢行進,故一腳向前微曲。此舉其實是為了能更全面地展示身上的紋樣,不難看出攝影師的取材構思更多是為了再現「入れ墨」這項傳統美術的榮光。

「入れ墨」(いれずみ)即刺青或紋身。刺青習俗在各個古老文明歷史中皆可見,尤以原始部落族群或少數民族為著。在這些文化中,紋身是不分男女老少的。

當伊薩貝拉更深入日本北海道觀察愛努人生活時,她描述:「愛努女人通常都會紋身,不僅在嘴巴上下刺寬闊的線紋,還會刺一條橫跨指關節的花紋,手背另有精緻的墨紋,以及一系列延伸到肘部的刺墨圖案。……女子直到出嫁之前,嘴唇上的鯨紋每年會持續擴大加深,手臂上的圓圈圖案亦復如此。」[2]紋身對這些日本原始社會族群而言,基本上出自信仰層面:「他們最關心這個問題,不斷說道:『這是我們宗教的一部分。』」[3]由此可見,日本原始社會對紋身概念有著鬼神信仰般的崇敬心態,在這樣的習俗行為中,紋身表現多偏向幾何或線性圖案,施色也較單一,蘊含著表徵性的作用。

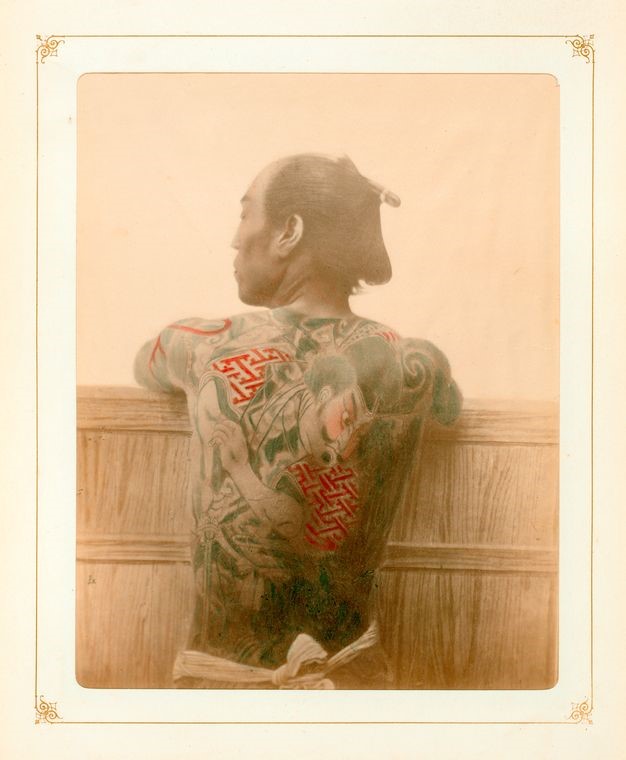

《男子與紋身》採取了人物背對鏡頭的上半身特寫視角,主角的個性無關緊要,但他背部精彩的紋身,讓我們聯想到浮世繪大師歌川國芳(1798 - 1861)筆下活靈活現的水滸英雄人物。

最先將形象化的刺青圖案發揮到淋漓盡致者,其實是浮世繪。

《水滸傳》在江戶時期(1603 - 1867)傳入日本,「義俠」或「義賊」的傳奇故事逐漸與日本戰國名將事蹟和固有武士道相互合流,鎔鑄成另一種活躍在江戶時代武士與民間低階層小人物(盜賊、地痞等)之間的故事,並聯結了英雄主義特色的文化內涵。國芳發揚浮世繪中的「武者絵」(むしゃえ)風格,其筆下豪傑人物不乏刺青武人。

有趣的是,浮世繪中的英豪身覆刺青,面目猙獰或威嚴,彰顯畫中人物勇武性格特點。這些英豪圖像本身作為當時日本人刺青的題材,他們將武士圖樣披在身上,象徵奮發無畏或忠勇堅忍的男性氣質,而這些刺青者大多是處於社會底層者。

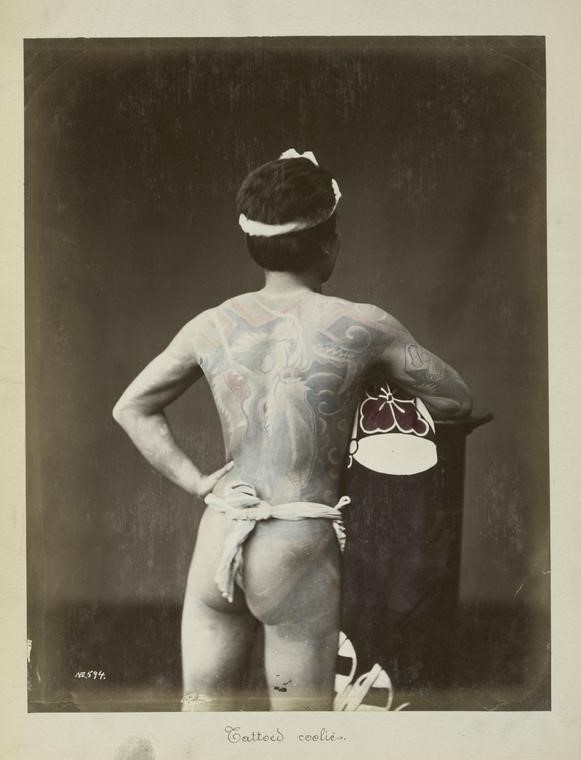

菲利斯.比阿托(Felice Beato,1832 - 1909)的兩張作品《別当或馬丁》和《奔走的別当》都採取了全身像。「別当」(betto/ bettoe, or running-groom)是馬車的隨行馬伕。美國牧師與記者 Edward Dorr Griffin Prime(1814 - 1891)曾在其著作 Around the World (1872)中敘述:「每台馬車都有位別当,他們實際上是男僕。在日本養馬的人都配有一位別当,他們是家中豢馬或路上行馬不可或缺的角色。⋯⋯別当與北美印第安人一樣是飛毛腿,他們能像馬一樣一日千里。他們裸著身體,腰間只繫著一條小布;然而,他們經常以彩色、紅、藍和其他深色調由肩到膝的渾身刺青來代替衣物,這也為他們帶來如畫般的外表。」[4]

菲利斯.比阿托二作中的別当正如 Edward 所述,他們只穿著一條丁字褲,身上紋樣展露無遺──有美麗的女子、龍等。一作以全背示人,另一作則以側身作行走態。作為一個在室外空間活動的社會角色──別当,他們被放在攝影棚中,去除了背景,僅以個別道具(如鞍具、拭汗巾)來表徵其職業特色。另一件《紋身的苦力》雖然顏色褪了不少,但仍可見手工上色的痕跡。苦力在職業類別上與人力車伕或別当無異,處於社會底層的他們負責搬運行李貨物或抬轎的工作。

耐人尋味的是,馬/車伕或苦力是當時從歐美遠渡重洋來到日本旅遊的西方人士,在踏上這塊土地時初次接觸者。他們幫西方遊客搬運行李,載著他們到處觀光與導覽,他們很大部分是西方人初臨日本的第一印象。旅遊觀光紀念照的販售對象是西方人士,其內容反映日本傳統文化在各方面的表現。因此,刺青者也成為攝影的題材。手工上色後的蛋白照片,更是將他們身上美麗紋樣淋漓盡致地再現出來。

浮世繪與 19 世紀日本旅遊觀光紀念照片的聯結,在許多地方皆有跡可循。多數浮世繪畫師都是著名的刺青師,他們在人體、手臂或腿部上作畫,並將刺青作為副業。所以刺青與浮世繪有著平行發展的脈絡,儘管江戶時期刺青是作為一種刑罰,但一些具設計感的紋樣仍在特定底層族群中流行。

19 世紀美國畫家約翰.拉.法爾吉(John La Farge,1835 - 1910)曾如此描述:「他們(指日本藝術家)的作品可與最好、最簡單的藝術表達方式相提並論,因其形式與時代同步,野蠻人的紋身與米開郎基羅的設計風格聯繫在一起。事實上,這是最接近藝術家意志的表達,也是藝術的根本。」[5] 受到日本美術影響的西方藝術家,隱射紋身與米開郎基羅畫中男性軀體美之聯結。在他眼中,日本紋身藝術家頌揚著男體之美。

日本刺青的社會觀感、定位及紋樣寓意,跟隨著時代流轉,當代刺青隨次文化流行,汲取傳統紋樣元素而多元豐富。這篇文章中我們僅觸及其中一個小面向,從西方人的視角來觀看旅遊紀念攝影中再現的題材與文化內涵,更全方位的考察與解析有待未來做更進一步研究。

[1] 中譯引自吳煒聲譯,《日本奧地紀行:從東京到東北、北海道,十九世紀的日本原鄉探索之旅》(新北市:遠足文化,2019),頁 60。原著引文:“The upper garment always flew behind them, displaying chests and backs elaborately tattooed with dragons and fishes. Tattooing has recently been prohibited; but it was not only a favourite adornment, but a substitute for perishable clothing.” 出自Isabella Lucy Bird, Unbeaten Tracks in Japan(London: J. Murray, 1888 [3rd ed.]), p. 34.

[2] 中譯引自:同上註,頁 367-368。原著引文:“They are universally tattooed, not only with the broad band above and below the mouth, but with a band across the knuckles, succeeded by an elaborate pattern on the back of the hand, and a series of bracelets extending to the elbow. …The pattern on the lips is deepened and widened every year up to the time of marriage, and the circles on the arm are extended in a similar way.” –,Unbeaten Tracks in Japan (London: J. Murray, 1888 [3rd ed.]), p. 259-260.

[3] 中譯出處同上註,頁 368。原著引文:“They are less apathetic on this than on any subject, and repeat frequently, “It’s a part of our religion.”,” p. 260.

[4] 原文:“Each carriage had a bettoe, who is literally a footman. Every one who keeps a horse in Japan has a bettoe, who is inseparable from the horse at home and on the road….The bettoes are as fleet of foot as the North American Indians, and will travel as fast and as far in a day as the horse. They are naked, with the exception of the little strip of cloth around the loins; but, in lieu of clothing, they are often tattooed from the shoulders to the knees in colors, red, and blue, and other dark shades, which gives them a picturesque appearance.” 引自 Edward D. G. Prime, Around the World: Sketches of Travel Through Many Lands and Over Many Seas (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1872), p. 98.

[5] 引文中「野蠻人的紋身」(the tattooing of the savage)應意指以武者繪作為紋身之圖樣。原文:“Their work can be compared to the best in this, the simplest means of expression in art, for in this all its forms and periods are united, and the tattooing of the savage is connected with the designs of Michael Angelo. In fact, it is the nearest expression of the will of the artist, which is the very foundation of art.” 引自Cecilia Wærn, John La Farge, Artist and Writer (London and New York: Seeley and Co., Ltd., and Macmillan, 1896), p.79. 另有關 John La Farge 對日本紋身的看法參照:Christine M. E. Guth, Longfellow’s Tattoos: Tourism, Collecting, and Japan (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004), p. 145; Hui Wang, “The ‘Bodyscape’: Performing Cultural Encounters in Costumes and Tattoos in Treaty Port Japan,” Global Histories: A Student Journal Vol 3, No 1 (2017): 89. 在 Hui Wang 的文章中亦有關於日本紋身文化與橫濱寫真的相關爬梳。