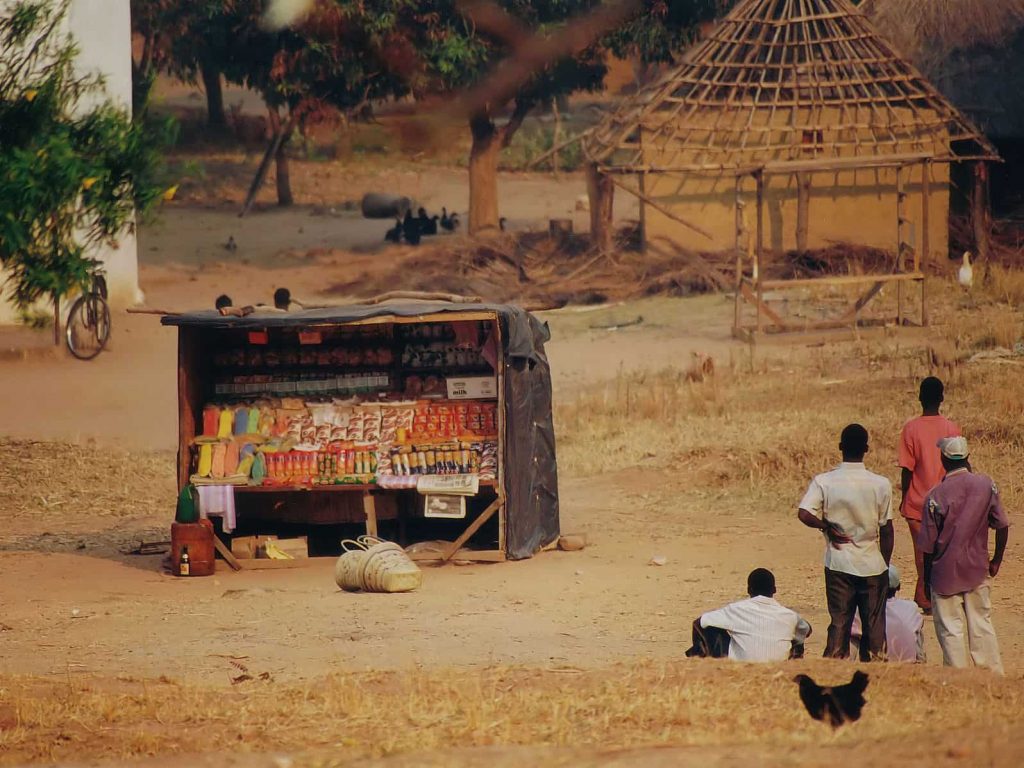

A dusty red-brown dirt road, scattered with huts and little shops, runs through the heart of the village of Kanchele in southern Zambia. At one end there is a lively market, and at the other, some villagers with Coke in their hands are idling away the afternoon playing pool, as clucking hens and their chicks scurry about.

In remote villages like this one, which can be found everywhere in Zambia, lurks a seemingly minor affliction that is, in fact, a killer: diarrhea.

On the other side of the world, in Taiwan, we cannot even begin to imagine losing a friend or family member to something as simple as diarrhea, but the dehydration it causes is actually the second-largest cause of death that contributes to one in eight children in developing countries not living to see their fifth birthday.

It is not at all difficult to prevent or treat diarrhea. Back in 1975, the WHO and UNICEF proposed an effective way to treat it in the form of an oral rehydration solution (ORS) containing glucose. Just one small sachet of ORS prevents needless death. The government of Zambia knows this and thus provides free ORS at nation-wide health centers.

That being the case, why is the death toll from diarrhea still high?

More than thirty years ago, when Simon and Jane Berry stood in front of a grocery stand in the Zambian countryside with Coca-Cola in their hands but no ORS in sight, they realized what the problem was.

If It Can Be Done with Coca-Cola, Why Not with Antidiarrheals?

In 1985, the couple went to northeastern Zambia as aid workers. There, they witnessed a neighbor lost a child to diarrhea.

To be sure, there were antidiarrheals in Zambia. However, due to the remote location, the bad roads, and the imbalance between supply and demand, basic medicines, including antidiarrheals, did not make it to rural areas. To obtain ORS, a mother whose child was suffering from diarrhea may have had to hike as far as 30 kilometers to get it. In contrast, Coca-Cola could be bought anywhere in Africa, even in the remotest of areas.

Simon explains, “No matter where you go, even in the remotest and poorest parts of developing countries, you can get things like laundry detergent, cooking oil, and Coca-Cola. So, if we can get these commodities to these places, why couldn’t we get simple medicines to those same places to keep children from dying from diarrhea-induced dehydration?”

He noticed that private-sector logistics were far better than public transportation, as evidenced by Coca-Cola. Even in places where there were no highways, local shopkeepers would transport crate after crate of the drink on their bikes. A brilliant idea occurred to him: If he could somehow get the medicine into those crates, then the medicine would be available wherever there was Coke. The demand for medical supplies would be met.

However, back in the 1980s, he was not able to tell the world what was happening in Zambia because information didn’t spread as rapidly as it does now and social entrepreneurship was barely a thing. As a result, Simon had no choice but to keep the idea to himself, waiting 20 years until it could finally be put into action.

In May 2008, he was invited to join “Business Call to Action”, an organization that is committed to solving social problems with businesses of all kinds, Coca-Cola being one of them. Simon hadn’t forgotten his idea from years before. Eager to find a way to establish a partnership with Coca-Cola, he posted his concept on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites. It was well-received, and Coca-Cola responded. The company contacted Simon and expressed their interest in partnering with him. Two years later, Simon and Jane quit their jobs and founded ColaLife.

Originally, Simon had come up with the idea that Coca-Cola could spare one spot for the medicine in every two-dozen crate. However, when put into the perspective of scale, one less bottle in every crate was not at all negligible. It would have been a lot to ask Coca-Cola to give up all that profit. Wasn’t there any other way to transport the medicine without Coca-Cola incurring losses? One day, Jane had an epiphany: What if they used the empty space in the crates?

It was the answer they had been looking for! Simon and his team designed a crush-resistant, wedge-shaped plastic container that fits perfectly between the necks of the Coca-Cola bottles in the crate. They called it AidPod and packed it with antidiarrheals and a pamphlet. The AidPod made it possible for the medicine to hitchhike in the crates without taking any space away from the product or increasing the cost of transportation.

By the end of 2011, everything was ready. A one-year trial that aimed to deliver life-saving medicine to rural Zambia began.

Beyond the Crate: A Lesson in Value Creation from Coca-Cola

The trial was successful. Locals welcomed the anti-diarrhea kits and, in twelve months, a total of 26,000 were sold.

However, there was still a critical fatal flaw. For every crate, only ten kits could piggyback along, which was far from enough.

With the arrival of each rainy season, the chance to contract diarrhea increased greatly and the demand for antidiarrheals was ten times that of Coca-Cola. If the kits continued to only come with the crates, many mothers would have to wait in desperation.

Moreover, while everyone was buzzing about the piggybacking, Simon and Jane discovered something surprising in the numbers: Only four percent of the kits sold in these areas had come from the Coca-Cola crates!

All of these findings meant that although piggybacking on the crates was indeed a clever and innovative idea, it was simply unnecessary and impractical for Coca-Cola to carry such a burden.

“It’s not the space in the crates that was important. But the space in the market,” says Simon, who began reconsidering the question Coca-Cola had asked him in the beginning: “What is the value chain of your product?”

More specifically, the question referred to how they would get vendors to sell the medicine and about whether everyone in the chain would profit from selling it. In other words, the ingenious packaging was only the start. 68,000 people in Africa worked for Coca-Cola at the time, but there were many more wholesalers, distributors, and retailers partnering with them. Their willingness to join the chain would be based on clear economic benefits.

This was the most important lesson Simon learned from Coca-Cola. “Coca-Cola doesn’t actually go into these remote villagers with their trucks. They make the products, they market the products, create a demand for it, and then the product is pulled into the communities because of the demand.”

The demand for Coca-Cola was such that wholesalers stocked up on the beverage and then sold it to distributors; the distributors, in turn, stocked up on it and sold it to retailers. Finally, the retailers sold it to the locals. “That’s why the last mile of the product’s trip into villages is on a bike, oxcart, or pickup truck.”

Once they found out what the problem was, the Berrys stopped thinking about how much more space they could make in the crates and turned their attention to creating value and making connections with local logistics operators and vendors.

There was indeed already a market for antidiarrheals in Zambia. Simon visited wholesalers, distributors, and even shopkeepers in rural villages, one of whom, a woman named Joy Munanyanga, immediately made a list of potential customers (including herself) and calculated how much she could earn from selling the kits.

After doing his homework and seeing the business opportunity, Simon decided that an anti-diarrhea kit would be priced at five kwacha (approximately 1 USD at that time). For every kit sold, the wholesaler earned 20 percent of the price while the retailer earned 35 percent. In addition, he tried to expand the market by giving out coupons and educating the villagers on personal hygiene.

ColaLife also worked with Zambia’s government healthcare agency to deliver the medicine from its central warehouse to different regions, and it then distributed the kits to the people who had signed a contract with Coca-Cola.

Simon explains, “Once we established a relationship with local merchants and consumers, we do not need to put the kits into the crates anymore. Now, wholesalers and shopkeepers stock the kits like they stock snacks, cooking oil, and laundry detergent. It was a huge step.”

Designing the Kit Based on the Actual Needs of the Locals

In addition to learning from Coca-Cola, ColaLife also lent an ear to what the locals had to say and tried to find out what people wanted. Before this, no one had ever asked the people in remote regions of Zambia what they really wanted.

Mothers told Simon and Jane that the government had been giving ORS away in sachets that had to be mixed with one liter of water, an amount which was too much for the average family because one child only needed 200 to 400 mL a day; the unused solution had to be discarded within 24 hours. This meant that both water, a precious resource in remote places, and medicine would go to waste. Another problem was that precisely measuring the amount needed from that one liter was difficult. If the child took too little, the medicine would not work; if he took too much, it would actually aggravate his diarrhea.

By working with the local women, Simon and Jane designed a new kit in which there were four sachets of flavored medicine to make up 200 mL of solution, which solved the problem of potential waste, difficulties with measurement, and aversion to the original taste of ORS by children; a 10-day course of zinc to prevent future diarrhea; and clear, simple instructions on the package to make it easy to use. Plus, a piece of soap was included as an encouragement for people to wash their hands so as to prevent diarrhea.

“We asked people what problems they had experienced in treating diarrhea,” said Simon. “I don’t think anyone had ever done that before. The kits were not designed for poor people; they were designed with them. You have NGOs sitting in their ivory towers thinking they are doing good, but how many of them give people the dignity of attention and choice?”

This is how the new design of Kit Yamoyo, a brand name that literally means “kit of life” in several African languages, was born.

To Sustain the System, You Have to Make Yourself as Unneeded as Possible

Another principle of ColaLife is to “respect local systems and not make yourself indispensable.” To keep the anti-diarrhea campaign going in the future, local organizations will have to learn how to do it by themselves since ColaLife won’t be around forever. If everything were always done for the locals, the whole system would crash once ColaLife withdrew.

Therefore, the Berrys made sure to minimize their presence, so ColaLife has no staff, no headquarters, and almost no tangible assets in Zambia. Many of the healthcare personnel and those in the value chain who sell the kits do not even know about ColaLife. The word “ColaLife” isn’t on the package. All of this is to make the system independent of the organization and sustainable by people in Zambia.

As a result of ColaLife’s efforts, the average distance a villager has to travel to get treatment is only one-third of what it once was, which means the medicine is easier to access and used much more. Based on their success in Zambia, ColaLife is planning to promote the system in other countries, making their self-developed anti-diarrhea kits the primary treatment for diarrhea in children.

Simon and Jane hope that someday it will be as commonplace to find the life-saving kits in rural Africa’s grocery stores as it is to find Coca-Cola.

A business organization that solves social, environmental, and welfare issues using its business model. For instance, a social enterprise may create jobs for the underprivileged and offer products or services that are socially responsible or eco-friendly. Profit made by social enterprises are used primarily for re-investment to continue solving social or environmental issues. Social enterprises do not work towards achieving maximum benefits for their investors or business owners.

Reference

- Official CoLaLife Website

- DefeatDD (2012, December 14), BRINGING COLA – AND LIFESAVING COMMODITIES – TO RURAL REGIONS

- Peter Day (2013, July 23), ColaLife: Turning profits into healthy babies

- Lisa Golden (2014, July 6), Piggybacking to success

- Deborah Kidd (2014, July 9), CATCHING UP WITH COLALIFE

- Wang Yu-Wen (王俞雯), ColaLife ,Taiwan Social Enterprise Innovation and Entrepreneurship Society (2015.9)